From surviving to thriving

HUMAN INTEREST

BY BRUCE STEINBERG

Betsy Hearne Claffey has lived her life as a loving daughter, wife, mother and grandmother; accomplished writer, editor and Ph.D.; teacher and mentor at the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana; former runner, ongoing walking enthusiast and yoga practitioner. In a retirement that is far from retiring, Betsy possesses all those wonderful aspects of a life well lived, and more.

Now, at 76, she has achieved a status using words you don’t often see together:

Pancreatic—

Cancer—

Survivor—

Ten years!

As readers of this magazine in which articles celebrate the silent, athletic movement of our bodies through nature, we all know what is out there—what can happen to any of us at any time, to our friends and family. Our celebration can be challenged, and taken from us at any moment, with news of a devastating diagnosis. Betsy has etched her experiences in her writing, including three poems worthy of close reading and re-reading. In sequence, they describe her journey, from diagnosis to survival, in words perhaps ironic because of their beauty.

In the beginning …

Operation

The days after death have pressed me and moved on

lie buried deep in a body slit and sewn. Incisions

ache with abandoned plans, memories of undimmed

energy. Nurses bring mercy with sharp needles.

Words no sooner read or spoken roll out of reach.

How will I find them, how will I walk the halls,

tied with tubes and draped with bags of liquid

dripping through veins? The pain eclipses

time but cells still multiply, malignant or benign,

as pulsing minutes open, close, open, close, open, close.

Betsy explained that her cancer journey began with abdominal pain which, she believes, “many do not discover the reason for until too late.” That could have been her fate, with doctors dismissing her pain as something treatable with antacids. After several tests, showing no cause for the pain, but the pain continuing anyway, a doctor told her husband of 35 years at the time, Michael Claffey, that his wife’s abdominal pains “were all in her head.” Michael, an active duty Marine in 1951-52, now retired journalist, university vice president, consultant and seniors tennis champion, knew that this doctor had no idea how tough Betsy is.

“She’s not an alarmist,” he said. “She insisted on one more test, and boom—the diagnosis. That doctor called the next morning to apologize.”

Betsy recalled. “I believe it was a second round of drinking barium and having the X-ray because pancreatic cancer grows so fast and can be easily missed early on.”

Daughter Joanna Hearne, a faculty member at the University of Missouri, describes her mom before the diagnosis as a powerhouse who had been Director of the Center for Children’s Books at the University of Illinois while leading a specialization in Youth Services at the graduate library school there.

“She was always working,” Joanna said, “critiquing student papers, giving talks, writing children’s and young adult books and staying up late to get everything done. She read everything my sister and I ever wrote. We still share all our writing.”

Younger daughter Elizabeth M. Claffey (“Lizzie”), who is on the faculty of Indiana University, agreed that “nothing can stop our mom. Just one foot in front of the other until she reaches what she wants to accomplish. She is both driven and vulnerable, with an elegant openness, a pioneering type of woman. A thinker who doesn’t feel sorry for herself.”

Lizzie continued, “At the time she was diagnosed, she was at the pinnacle of her career, with a long life of succeeding at her profession, academically and creatively, and was ready to turn her attention to focus on more writing. The diagnosis was a surprise because, eleven years younger than Dad, it felt like Mom was supposed to live forever, longer than Dad.”

As to doctors who were dismissing her mom’s unexplained abdominal pains, Lizzie says her mom had an “I-will-figure-it-out” attitude.

“When a doctor said, ‘She’s just getting into a tizzy over nothing,’ Dad stepped in and said to the doctor, ‘You don’t know this woman. If she says it’s happening, then it’s real!’ and Mom persisted with ‘Test, test, test,’ until, finally, the true diagnosis was discovered.”

Surgery

Bonus

When your oncologist says that death

is a mystery, minutes begin to sing.

Whoever is in charge of such things,

thanks for giving me a day. The wind

blew from the south

and I had a good lunch.

Either would have been enough.

Pancreatic cancer surgery is often called “the Whipple Procedure,” perhaps a too light-sounding name for such a grievous assault on the body, but so-named after American surgeon Allen Whipple, who improved and refined the surgery in 1935. When you hear that it involves removing the head of the pancreas, all of the duodenum (the connection between the stomach and small intestines), proximal jejunum and pylorus (also part of the small intestines), gallbladder, often part of the stomach, and area lymph nodes and also exploratory surgery of the liver and peritoneum (the membrane covering the abdominal organs), it’s easy to see this surgery as a Roto-Rooter of the body. Medically listed as a “pancreaticoduodenectomy,” the procedure begins with the exploratory look at the liver and peritoneum because the Whipple cannot be done if the pancreatic cancer has metastasized to those regions. This is the case 80 to 85 percent of the time. Of the remaining 15 to 20 percent, 5 percent do not survive the surgery itself. Typically, the procedure lasts six to seven hours. For Betsy, it lasted 14 hours because of an unexpected blockage in her celiac artery.

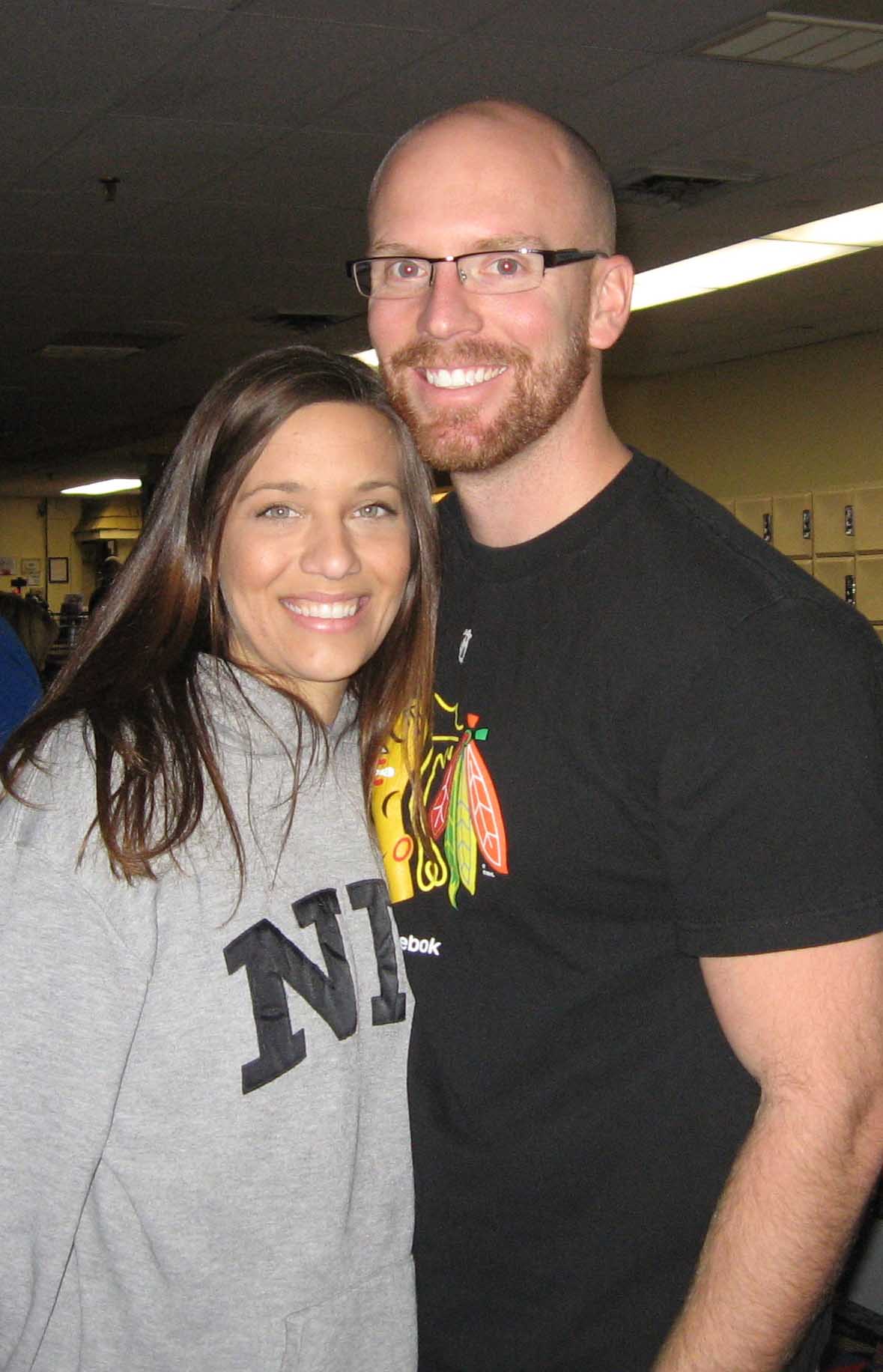

This photo was taken soon after the Whipple procedure, with Betsy recovering while daughter Joanna is at her bedside.

“When I got the diagnosis,” Betsy said, “it was a Wednesday, and I had to appear in a video that afternoon. My surgeon, Dr. [Sherfield] Dawson at Carle Hospital in Urbana, Illinois, scheduled the Whipple for Monday in spite of the oncologist’s preference to delay it for more tests. I can’t say I was scared because I had so many things to do, so many commitments. I had retired from the University of Illinois a year before, but I was in the midst of finishing a book with a colleague, and I always did creative writing along with editing others’ work, although it turned out after surgery that I was too weak even to read proofs.”

“I purposely didn’t look at the statistics for pancreatic cancer,” Michael said, “although I knew survival was in the single digits.”

Lizzie was in Maine working when she got the phone call from Betsy.

“Mom wasn’t crying,” she said, “and told me without hesitation. I had no idea about pancreatic cancer at the time, but I understood it was scary news. Mom approached it like a project, like a book. She embodies both toughness and empathy, but her emotions never get in the way of getting the job done. I wasn’t afraid that my mom would die, but I feared her living with extraordinary pain. She would be at peace with death because she knows her family loves her, and that her life has been rich. Still, I had a naïve confidence that she wasn’t going to die.”

Joanna had similar thoughts.

“Leading up to the surgery,” Joanna said, “my mom had just retired but was still active and busy, involved with the university and writing projects; with the diagnosis and surgery, she was separated from a lot of that. And she’s the center of our family—we were not ready to lose her.”

Post-surgery recovery – death at the doorstep

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) is a bacterial staph infection resistant to antibiotics. While the Whipple seemed to have gotten the pancreatic cancer, MRSA was one of several post-surgical setbacks that threatened Betsy’s recovery—and her life. She also faced down pneumonia, the undoing of wire stitching, gastritis and starvation syndrome.

“Betsy’s discipline is staggering,” Michael explained. “She learns and then follows what she learns. With fifty-six days in the hospital post-surgery, fighting MRSA and other problems, her determination to ask study, learn and take advice is a big reason for her survival. She took care of her mother when she became ill, and that, too, may have prepared her for her fight. Like that, Betsy took care of her rehab. While in the hospital, in extreme physical pain, she studied research papers on cancer rehab, diet, exercise—even the morning after her surgery, she had a pad and pen and asked Dr. Dawson, ‘Show me what you did.’ Dr. Dawson then sketched what he had taken out, and Betsy said, ‘Thank you,’ knowing she was learning her plan for recovery. A particular book, too, called Anti-Cancer, a New Way of Life, by Dr. David Servan-Schreiber, was always with her.”

Betsy also talks about her post-surgery recovery.

“That book became my Bible, and I read it constantly and recommended it to others,” Betsy said. “I also had experience with this. My father, both grandmothers, an aunt and uncles had all died of cancer. A brother who died of Alzheimer’s had had melanoma. That first morning, I clearly remember taking notes, but I was having hallucinations, trying to write them down, about how to save the world in three questions. Too bad they turned out to be illegible! It helped to have a sense of humor, especially since I was in the hospital for my 66th birthday. Throughout my two-month hospitalization, the nurses were fantastic, so caring. My recovery involved wound-packing, something done on battlefields and now commonly everywhere, in which deep wounds are not simply stitched over because that increases the risk of infection within, but are packed and repeatedly repacked to heal from the inside out. It was agonizing but necessary.”

The nurses went out of their way, holding Betsy’s hands in the night.

“One night in particular,” she recalled, “I saw a light coming closer to me. I was half out of my mind with pain meds and MRSA antibiotics, which thankfully, the right combination had been found to beat. That white light, you know, the classic image of near-death, turned out to be nurses, with candles on a cake they carried, singing ‘Happy Birthday’ to me. I had no breath to blow out the candles, so the nurses did. The next morning, another group of nurses brought me a cake but didn’t light the candles because of all the oxygen supplies in the room, something that didn’t seem to bother the night shift nurses. Not that I would tell because I was so appreciative of all this goodwill.”

Joanna also talks about her mom’s recovery.

“My mother,” Joanna said, “made her recovery with courage and incredible determination, by studying and listening to her body. Michael was always there taking care of her and protecting the quiet she needed to recover. It was a five-hour drive for me to visit her, so I could come on weekends. I didn’t focus on what might happen later—I wanted to know how she was doing that day. What could we do to help her right now? I talked with Michael, my sister or my mom every day.”

Lizzie said that her mom didn’t want her and her sister there for the surgery.

“Especially since I was just starting my master’s program, and she was adamant that we stay focused on our work despite her diagnosis,” said Lizzie. “Two weeks after the surgery, my dad suggested that my sister and I come for a visit. She was laid out, covered in blankets and unable to communicate. Being unable to talk to her was challenging – my mother, sister and I have almost daily phone calls. We are ‘the Hive,’ as my brothers-in-law coined it. We are always in consultation with one another. My brothers, Michael and Cyrus, were concerned almost as much for Joanna and me as they were for my mom. I remember my father telling me that one of the first things they asked after hearing about my mom’s diagnosis was, ‘How are the girls doing?’ I knew then that I was either going to drink my way through this or use my education and passion to photograph my way through it. Mom was in favor of the photographs, so that’s what I did.”

Ten years of recovery

“My first thought about Betsy,” said Lois Steinberg, Advanced 2 Certified Iyengar Yoga Instructor (Iyengar Yoga, Champaign-Urbana), “was that she would be one of those people who would be dying. Like bed rest a doctor would prescribe, Betsy then needed yoga rest.”

Not knowing each other, Betsy had been referred to Lois by a deep tissue therapist, but Lois knew her circumstances.

“Her skin was pallid, her eyes without light, her posture concave and a damaged liver fouled her breath,” Lois said.

Betsy took all of Lois’ recommendations to heart.

“The surgery left my body twisted, with nerve damage,” Betsy said, “Wires left in me for almost a year after my surgery had to come out, which involved more infection. I remember very clearly that, with yoga and my studies in Buddhism, I wanted to learn how to live beyond the medicine, to live as well as possible with the time I had left. Lois gave me resting postures over the 90-minute sessions that I also practiced at home. It was a time when I felt there was always something going on and going wrong, and I teared up during an early session. I didn’t realize, but Lois saw it and took me to a private room for quiet breathing, which is what I needed. Lois gave me what I needed to live with what I had.”

Lois also remembers those early days of recovery.

“When she came back to yoga after her wires were removed,” Lois said, “she was still very frail, but I saw she was living, not dying, with a glimmer to her eyes and color to her skin. Betsy’s a reflective person, a poet. It still took about a year before she was ready for more active yoga poses, to allow her body to build back up, but she began to look robust, with a rosy skin tone and clear eyes, and her chest became convex instead of concave and she has regained one-and-half inches of the height she lost after her surgery. Now she is at the peak of her game, taking two group classes a week, plus practice at home. Throughout it all, Betsy was as determined with her recovery as she was with her diagnosis.”

For Betsy, these days, yoga and Buddhist meditation practices have helped bring her peace, strength and joy.

Michael cannot help but agree.

“I absolutely believe that yoga with Lois helped her recover and continues to be an important aspect of her life,” he said.

But it’s Betsy’s attitude, he added, and what she brings to everything, not just yoga.

“Every day is a challenge to her. Although the surgery left some of her pancreas intact, she eventually lost that function, too, and she has to deal with being a diabetic,” he said. “With her meds, exercise, diet and everything she does, Betsy does not complain. It’s a test, a struggle and she passes the test every day. Even the moments when she doesn’t feel well, she takes a walk, meditates, does yoga and invariably feels better. And, at 76, she keeps a full schedule. She edits for extremely complex writers, including Joanna and Lizzie. She mentors and does her own writing, including essays, memoir, fiction and poetry. She just gets on with life.”

Joanna sums up her recovery.

“It was a long and slow,” Joanna said, “I don’t think there was a defined, specific moment where I thought things had turned around. Leaving the hospital, she was still really fragile. Six months later, she could eat pretty well. Then she had gastritis and other setbacks. She was so strong and determined, taking what she learned as a researcher to remake herself, and she’s still the amazing woman she has always been all my life.”

Lizzie summed up her mother these days as a woman who is “nailing old age, with grace and hard work, because she is who she is, older but still putting one foot in front of the other.

“The thing is,” Lizzie explained, “she knows to forgive herself for being sick, that if she doesn’t feel good one day, it doesn’t mean overall that she’s not good. She no longer feels she has to work ten-hour days or more in an office. With her recovery, she has closed past doors and opened new ones – yoga, walking and meditating – and these are not sentimental practices; to her, they are life-giving work. Work in the best sense.”

Betsy concludes.

“I just didn’t believe I would die,” she said, “even though death was my constant companion. Knowing death can happen at any time somehow eased my fear of death because now I was going to live every minute. At 76, I am an old lady, lucky to be old! And I’d like to think my third poem reveals that feeling.”

Zen Prize

If it’s now,

You’ve won.

What you’ve won

is now.