Get over the ‘Not me, not today’ syndrome

No one is immortal on the water

by Darren Bush

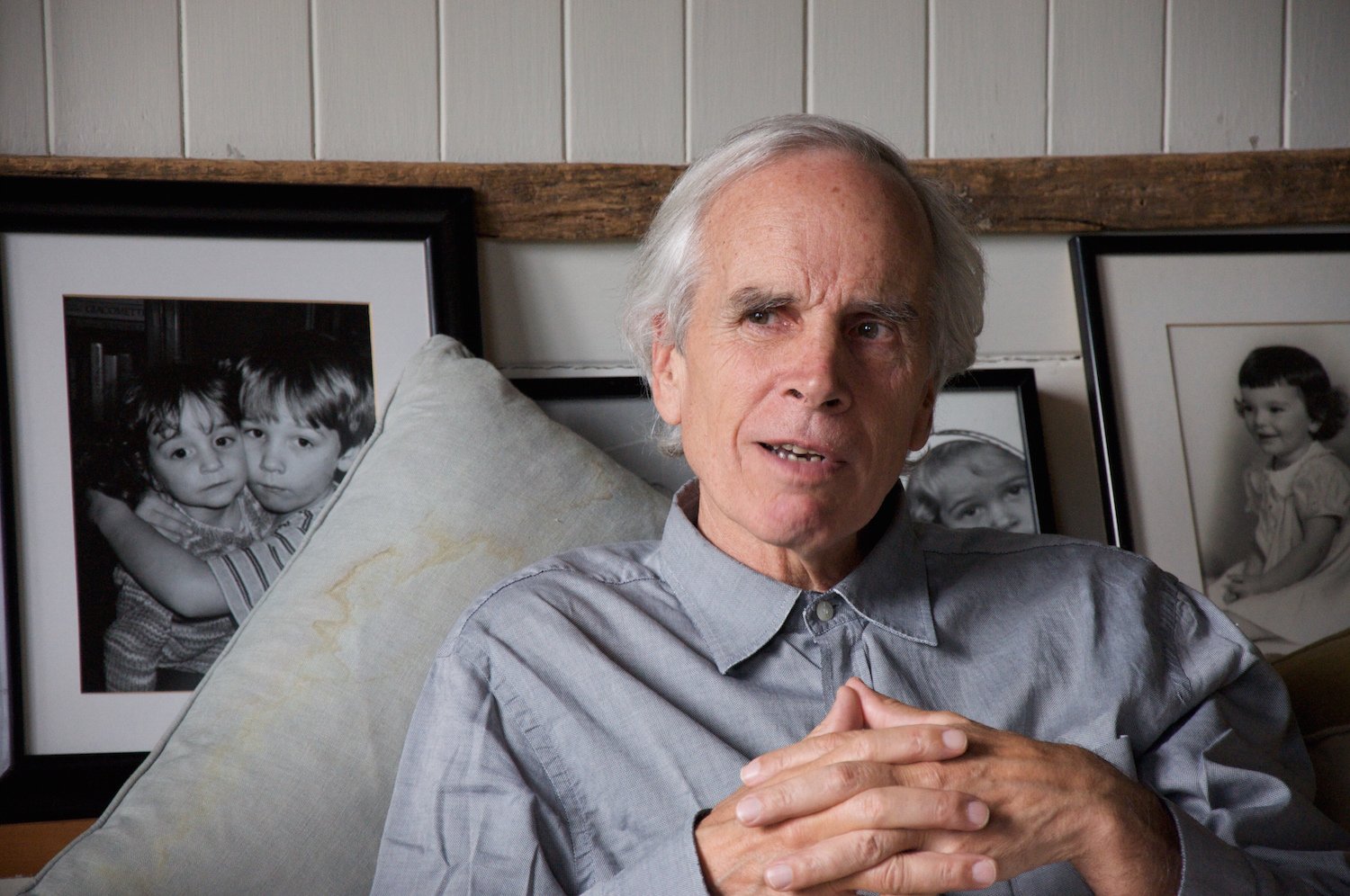

Doug Tompkins, founder of The North Face. mountaineer, expert whitewater kayaker, credited for numerous first ascents on three continents, bush pilot. In short, an outdoor expert to rival almost anyone.

Doug made my first sleeping bag. He made my first good tent. He is one of the reasons I am a child of the outdoors.

Now, at 72 years of age, he’s dead.

The reports of the December 8 accident continue to come in, and with that, more details. But the simplified version is this: Tompkins was with five other expert kayakers in a total of three tandem kayaks, noted for their stability. They were paddling on General Carrera Lake in Patagonia in Chile, a lake about three times the size of Lake Champlain on the Vermont-Quebec border. The wind came up and capsized the kayaks. The water was under 40 degrees. A broken rudder kept Tompkins’ boat from heading toward shore.

They were not dressed for immersion. Tompkins was wearing a paddling jacket.

Chilean rescue teams with helicopters managed to get everyone out of the water, but Tompkins spent two hours in 40 degree water. His core temperature was about 75 degrees. He died at the hospital. The other paddlers were treated for hypothermia but survived with no permanent injuries. They are lucky to be alive.

It’s easy to cast blame. Why were they not wearing drysuits or at least neoprene? No one should ever paddle in water that cold without being properly clothed. They should have known better. They were experts, for cryin’ out loud. Facebook is suddenly populated entirely by paddling experts who want to show how much smarter they are than Yvon Chouinard, founder of the American clothing company Patagonia, who was also on the trip.

Nonetheless, I can’t blame them. I can’t blame them because I have done the same thing. Most paddlers have. I could say all paddlers have and I’d be mostly right.

I can also state for a sure fact that every paddler who has ever taken an unexpected swim didn’t think they were going to get wet. That’s why, when wet they get, it’s unexpected. I don’t board a canoe kayak thinking “Well, I’m not going to get wet today. Tipping over is for people who can’t paddle.”

I have tipped a handful of time in the last few decades. But every time I was dressed for conditions and immersion. I’ve taken a swim in near freezing water where all I had to do is climb out of the stream and dry off, get something hot in me and change my clothes.

But I’ve also done crossings where I had no business being dressed the way I was. Long ones.

The fact is, when kayakers and canoeists die, it’s when they’re not dressed for the weather. They are not prepared for conditions. It’s because they don’t think it’ll happen to them. Not today, anyway. Not me, not today.

It can happen

I can only describe my own experience, but I can tell you that the times I have been underdressed were times when I was more concerned about discomfort than dying. Neoprene will save your bacon, but is hardly comfortable. It’s a lot better than it was years ago, but still, a four-millimeter layer of non-breathable insulation on a hot summer day is just plain nasty.

Meanwhile, just under your butt is water that is 40 degrees colder than the air and capable of sucking heat from your body 25 times faster than the air.

But you’re not going to tip over today. The sun is shining. Sand Island, one of Lake Superior’s Apostle Islands, is only a mile and a half away and there’s no wind. You don’t want to put on your drysuit, and you’re paddling a stable boat with three other good paddlers. The chance you’ll be in the water for more than a minute is slim.

Then the wind comes up. Little Sand Bay, part of the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, is exposed to 50 miles of open water and becomes shallow quickly. All that water piles up and creates nasty waves. One of your group is feeling seasick so you raft up. But you start getting blown out into the bay. You try to tow each other back in but the wind keeps building and the waves start to break over your decks. The temperature drops 10 degrees in an hour. It stopped being fun a while go.

This is one of those times you wish you were wearing your smelly old neoprene. Or your drysuit, the neck gasket of which is a little tight. But it’s too late to put either on.

Then one of the other paddlers in your group starts to feel their blood sugar crash but their GU or candy is in a dry bag in another boat. The problems start piling up.

Few people die from making one big mistake. It happens when a series of small, almost insignificant decisions compound into an escalating mess. Launch rather than wait.

Paddle jacket instead of dry top. Hat left in the car. GU not accessible. Weather radio in the car. A leaky sprayskirt.

Please remember, gentle reader, I am speaking to myself here. Paddler, heal thyself.

“Not me, not today.” We all say it in our heads. How do we overcome this natural tendency to think we’re immune to what puts everyone else at risk?

This is what works for me.

Thinking of family, the author’s daughter, Whitney, kayaks Lake Superior in a drysuit. PHOTO BY DARREN BUSH

Think of family

I think of my family. I love my wife and children. And I, as of this moment, believe they love me. I think of a park ranger or worse, a dear friend, making that phone call no one wants to make or hear: “I’m sorry, but your husband died of exposure.” Because he didn’t take necessary precautions that would have saved his life, actually.

Think of friends

Do you want your friends hauling your body out of the lake? Or do you want to be the one calling 911 or the U.S. Coast Guard and dealing with a friend and paddling partner who has become a cold, lifeless piece of clay? No, you don’t. I promise you that.

Think of yourself

That is self explanatory. Except it isn’t. The world is better with you in it, despite what you might think. If you don’t think so, that is a conversation to be had with mental health professional.

Think of paddling

Every time someone dies in a kayak, the world thinks kayaking is dangerous. Never mind that the person who perishes likely had little training and was in the wrong boat in the wrong conditions. It doesn’t matter. We want people to love what we love. The general public does not differentiate between a couple of inebriated college kids who borrow a boat and flip at midnight and a trained kayaker who makes an error in judgment. To them, kayaking equals danger.

Use checklists

I don’t claim to suffer from Attention Deficit Disorder. But I assume that everyone around me does. I need a checklist or I become a liability to my fellow paddlers. What’s funny is I tend to be more concerned with other paddlers than myself, which is dumb because I’m no good to anyone in the water, cold and getting colder.

Make decisions before you need to

When I was a kid, my parents would tell me that making a decision now was easier than making one later in the heat of the moment. It was easy for me not to take drugs in high school because I made the decision not to long before I was asked by someone at a party, “Hey, wanna toke?” For the record, I went to high school in southern California where more people smoked pot than tobacco.

So decide now that when the water is under X degrees, you will wear insulation, period. Then when the water temperature is 59, and you have decided that X=60, you will put on your insulation. You don’t have to think about it. Don’t say “well, 59 is close to 60.” You just put it on. Every time.

Of course, none of this works if you don’t take it seriously. Get over the “not me, not today” syndrome, and stay alive to paddle another day.

By the way, we miss you, Doug. Thanks for all you did for us. For me.

Darren Bush is owner and chief evangelist of Rutabaga Paddlesports in Madison, Wisconsin.