The Lure Of Gravel

Bicycling with Walter Rhein

At first, I scoffed at the idea. Riding 100 miles on gravel? What’s the point? Riding 100 miles on pavement is hard enough. Even when I run on gravel, it’s slower, the ground sinks with every kick; on bicycles, your tires spin out and send up clouds of choking dust. What is the lure of gravel?

I resisted, even though my friends returned from Almanzo with mysterious white dirt in every nook and cranny of their machine. In pictures, too, they’d show up caked with dust, looking like ghosts of ’20s era Tour de France riders. People would approach these Spring Valley veterans at other events and say, “Ah, Almanzo dirt.” Then share a nod that bespoke a fundamental bond beyond what further conversation could forge.

So finally I broke down and traded in my Trek OCLV Carbon for an Aluminum Crossrip LTD. The bike struck me as heavy at first. The knobby 35 mm tires looked like balloons. I loaded this beast onto my rack and made the midnight drive to Spring Valley to partake in the Almanzo.

Thirty seconds into the event, we hit the gravel and I fell in love.

Like most things cycling, it’s not just the ride or the miles or the challenge, it’s all of these things, but most of all—the camaraderie.

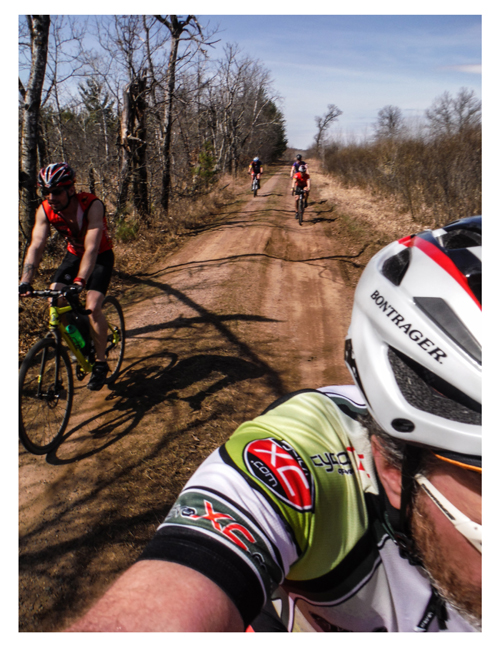

Gravel riders are not like other riders, they’re the most mellow of the bunch. They’re the type of cyclists with beards and wool jerseys. If road bicycles are sports cars, gravel bikes are motor homes. There’s more personalization, stickers and fenders and homemade frame bags. Gravel riders look like they could live on their bicycles for a decade, they could find nourishment in sticky burrs and pine cones if doing so bought them the privilege of riding three more miles.

I like the fact that speed is no longer the driving force on gravel. Sure, it is for some, but the completion of the event is the ultimate challenge. Cruising along at 11 or 10 or 9 miles per hour is not met with disdain. Sometimes the sand grabs you and turns you sideways. Sometimes the road sinks. Sometimes it’s flooded. There’s no way to predict what you’ll encounter, so your focus must be on the adventure and not the vague concept of a PR.

Almonzo gravel is like pavement, but your spinning tires kick up a cloud. Early on the pack surrounds you, but late in the day the riders go single file along a narrow ribbon of packed earth. In those inevitable moments of solitude at the end of a century, your focus becomes the narrow hard-packed track stretching off into the distance indicating the exact path of everyone who came before.

Wisconsin gravel is much different. It’s softer, more difficult to traverse with bigger stones strewn about. Every event has a calling card. At the Mammoth Gravel Classic in St. Croix Falls, you must deal with the sand barrens. Several miles of sugar sand which you have to surf through. At the Skull-N-Bones in Bruce, you have to deal with the Tuscobia trail. Tuscobia is a “shared use” trail, and if riding Tuscobia for 10 miles in the summer doesn’t convince you of the need for separation of motor and bicycle, then nothing will.

I recently did the Mammoth with Dan Woll, author of North of Highway Eight. It was his first time at this event, but Woll has ridden a lot of miles. From Leadville 100, to climbing El Capitan, to hammering out 24-hour endurance challenges, Woll has stamped his adventurer card. The first 15 miles of Mammoth is pavement, and Woll started to grumble. “If I’d known it was going to be all pavement, I would have brought my Ma-Drone.” It took me a minute to realize he was talking about a Trek Madone. Instead he was riding 1982 technology, a busted up 26er with a broken suspension fork; thus he had all the weight and none of the benefit.

Gravel is fickle, you find it where you find it. We took our first turn onto dirt after an hour and the canopy of trees created an effect similar to entering a cathedral. The first few moments, you assess what you’re in for. How sandy is it? Is there a firm base? Will my tire get caught in a rut and kick me to the ditch?

These calculations are factored into your innate cycling algorithm. Calibrations complete, you focus on the beauty.

Woll was stunned. A loquacious man, all he could manage was, “What a beautiful road.” Then silence. Then, “What a beautiful road,” again.

The first patch of gravel only went a few miles and kicked us out onto pavement. It was like sitting through a preview at a movie, but we were left even more excited about the upcoming feature. “People would come from hundreds of miles to ride that,” Woll said. “They’d pay to ride it.”

Then on to the barrens where we were forced to slip and slide through sand. Some patches had been blown wind flat to the hard base, but other sections were traps. You could see the traps coming from the tracks of the previous riders who had dug so deep with spinning wheels that wet, brown earth had been spun up from below. Here, Woll was happy to have his 2.2” tires. On 35 mm’s, I had to put my foot down on occasion. Riding soft sand is a matter of balance, you can’t allow too much of your weight onto your handlebars or you’ll go right down. Sometimes you begin to spin like the roadrunner, slowing to a near stop before a knob catches and you propel forward. If you tumble over, no worries, the sand is soft and you wear the dust on your jersey like a badge.

The prospect of a hundred miles of sand is enough to collapse your will, but the thing to remember with gravel is that it’s never the same for very long. At Mammoth, we went on to fire lanes, gravel roads, and finally the Gandy Dancer (Trail). The enchantment of gravel is that you get to the quiet places on trails that can be described as something between a road and a path. The grass is at your feet, not distant beyond the shoulder in the ditch outside your peripheral vision. When you put your feet down on a gravel ride, you often put your feet down in grass.

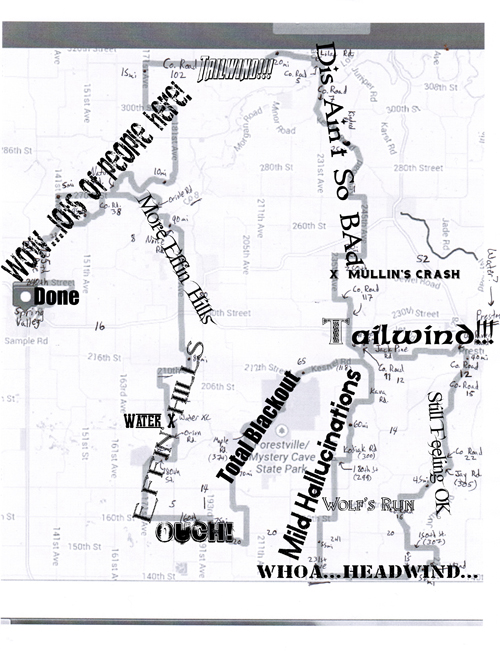

Gravel rides are free for the moment, although litigation will probably ruin that eventually. Rides pop up throughout the summer, most on grassroots budgets. Almanzo is the grand-daddy of them all and brings in thousands of riders. Generally you’re offered a cue sheet, but I always scour the route to create a “bail-out” map in case of emergency. Late in the day at 90 or so miles when exhaustion has set in and you can think of nothing more than a hot shower and food that doesn’t come in a packet, it’s easy to miss a turn and add 10 devastating miles. Such tragedies make for great stories.

The best part of gravel is that the roads are less traveled. I’ve been cycling for close to 30 years, and if I never encounter another motorized vehicle while I’m on my bike, that will suit me just fine. Sometimes you can ride on gravel all day and not even hear a motor. The thunder of that silence is gratifying.

But don’t take my word for it, go check out a gravel ride yourself. The best part is, many of these events publish their cue sheets on their web page giving us a host of adventure routes to choose from. Visit the web pages. Gravel riding is still a relatively new kind of bicycle adventure, but there are those who say it is the best.

About the author:

Walter Rhein is the author of “Beyond Birkie Fever” and “Reckless Traveler.” He can be contacted for questions at: [email protected].